This past Saturday, I spent the day in the beautiful outdoors a few hours from Tokyo hanging out with a small group. Most of our time was spent meditating, hiking barefoot—or more poetically, 'kissing the earth with our feet'—and plunging into freezing-cold snowmelt waterfalls.

At one point, we all scattered to find our own little nook to meditate. I sat down next to the river. As I extended my legs, a swarm of little black bugs came to feast. I’d never seen these particular bugs before. They looked like a mix between a small beetle and a slug...with wings.

I’ve reached a point in meditation where most things no longer bother me during a sit. Squealing pigs, chainsaws, snoring, ants, spiders, and unrelenting itchiness—just to name a few things I’ve sat through. When everything becomes a 'practice in awareness,' there is a level of acceptance that becomes easier to drop into.

But still, these little black bugs were freakin’ relentless. They just kept flying onto my legs and occasionally biting me. The pinching sensations gave me little jolts as I tried to stay centered and calm. I continued with eyes closed and a half-smile, slowing my breathing down, and eventually fell into a deeper state of meditation.

After a few minutes, I noticed that the pinching and buzzing had stopped. I peeked to make sure I wasn’t just imagining things. Nope...there were no more insects anywhere on my legs or body. Were they just passing through? Or was there something about my meditation that somehow repelled them?

I began to wonder.

The Thai forest monks

Meditation master Ajahn Chah was sitting quietly in the dense Thai forests when he was approached by a deadly cobra. Because of his stillness and radiance of loving-kindness during deep meditation, they say, the snake slithered away. He lived to tell the tale.

In fact, on another occasion he was approached by a tiger who, story goes, peacefully observed him and then left. Other people talk about how deer would often gather around Ajahn Chah, seemingly drawn to his tranquility.

There are more such stories in the Buddhist texts. Like when the Buddha was approached by a big, angry elephant, and to the amazement of bystanders effectively deflected it with the power of his heart.

I asked the AI-chatbot developed by one of my teachers, which is effectively like tapping into the Buddha-brain, and it responded with the following:

“These stories illustrate the transformative power of loving-kindness. When we cultivate metta, it can create an atmosphere of peace and goodwill that can influence others, including animals. However, these are exceptional cases and should not be taken literally.”

Wise words. Relying solely on your meditation powers to ward off predators is risky business. One Buddhist monk in India found out the hard way when he was attacked and killed by a leopard during meditation.

There are probably many stories where the outcome wasn’t as rosy.

Anyways, you won’t find me sitting next to any cobras testing this theory. Still, I think there are reasons why animals and insects might avoid meditators more than non-meditators. If true, this means that I don’t need to waste money on insect repellent that never seems to work anyway.

Let’s explore…

Reduced carbon dioxide output

Many insects, mosquitoes in particular, are extremely sensitive to changes in CO2 levels in the atmosphere. They can detect CO2 from up to 50 meters away and use this as the primary mechanism to find their hosts, including humans and other animals.

In deep meditation, the heart rate and breathing slow down. Metabolism decreases. The demand for oxygen decreases and so does your CO2 output! If you are dropping your CO2 levels, bugs might be less able to detect you.

Or, at least if the bug is scoping out 5 potential hosts and 1 of them is in deep meditation and the rest of the group is huffing and puffing, then the bug would choose the most out-of-breath host expelling a bunch of CO2. Sorry, all you walking meditators…

Not smelling like rancid butter or cheese

Since I don’t know what the black bugs were called, I am going to continue to use mosquitoes as my primary example here (and because mosquitoes have been widely studied). One study on what attracts mosquitoes found the following:

“The mosquitoes were especially beguiled by carboxylic acids, a class of fatty acids found in human sweat whose scent is sometimes compared to rancid butter or cheese.”

I don’t know about you, but depending on my diet and routine, I’ve definitely gone through periods where I smelled like rancid butter or cheese. Exercising intensely makes this very apparent.

Mosquitoes are attracted to smells of lactic acid and ammonia, released when you’re breaking a sweat. So, when you’re sitting still, all relaxed and chilled out like a Buddha statue and not excreting cheesy smells, they won’t be able to pick up on your scent as easily. (Of course, it depends on the temperature if you’re outdoors).

And then there’s vibrations

The less movement you make, the less detectable you’re going to be. I’m reminded of the scene of the ground-shaking as Godzilla approaches. That’s probably what it’s like for many animals and insects. They get scared off by our loud human footsteps and talking.

That means sitting perfectly still for minutes or hours on end, you’re just like a tree in the forest. While not specifically attracted to you, some insects and animals might cross your path because they didn’t hear you. The cobra, the deer, the lion, and the beetle might come right next to you or walk right past you as there is no threat detected.

For insects at least, it might make sense that if you’re not smelly, not emitting too much CO2, and not moving, this creates the right circumstances where a bug doesn’t even notice you; or it lands on you and then quickly moves along.

Bu what about predatory animals?

A heart-centered forcefield

When Ajahn Chah was sweating it out in the Thai forests, he was probably still being devoured by mosquitoes. And yet, he managed to avoid being attacked by the cobras or tigers. Was it the power of his metta, or loving-kindness, towards all beings?

When I was 12, I remember buying a large book called Cymatics (full PDF here) that shows how sound vibrations can create intricate patterns in water, sand, and other substances. The lesson for me was clear: vibrations affect the matter around us.

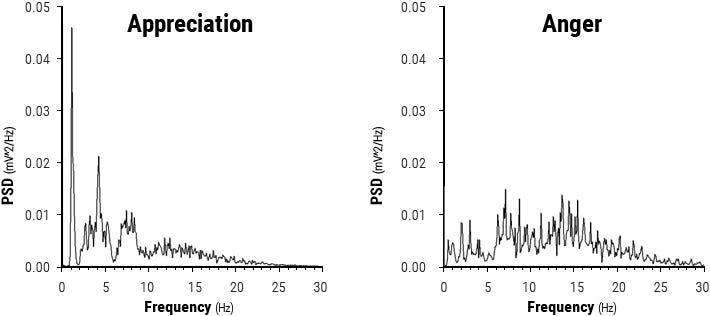

In fact, the heart produces the strongest bioelectromagnetic field in the body, which can be measured from several feet away. Studies show that positive emotional states actually change the electromagnetic frequency of your body. Anger looks different than appreciation.

If you’ve ever been in the presence of a kind, saintly person, you can feel an aura that can’t be explained simply by their smile (an old professor I had and some meditation teachers come to mind). The Heartmath Institute came out with a lot of fascinating studies that suggest that the frequency of your heart can impact the brainwaves of other people, even without talking or physical contact!

“The results of these experiments have led us to conclude that the nervous system acts as an antenna, which is tuned to and responds to the magnetic fields produced by the hearts of other individuals.”

If this is really true, then why not other animals too? It could mean that a meditator in a deep state of samadhi that is opening their heart wide could potentially alter the brainwaves of other creatures passing by. The state of your consciousness can have a real tangible impact, even if you’re not doing anything.

Writing this reminds me of the interconnectedness of all beings. We impact each other and our environment not just through our actions, but by our mere presence and the state of our consciousness!

Another explanation - Playing Dead

And yet, there is another fascinating idea I heard from a yogi. When you are in fight-or-flight mode, your sympathetic nervous system is activated. Your heart rate is going to increase, temperature increases, and your muscles are going to tense up.

Conversely, when you’re in a deep meditative absorption state called 'jhana,' we know that your body’s nervous system shifts into what’s called a dorsal vagal state. All mammals have this capacity to go into the dorsal vagal, which is also known as a 'freeze' state.

The deeper end of the dorsal vagal, or freeze state, is the fawn or playing dead state! When a cheetah catches a gazelle, the gazelle might play dead. When the cheetah is momentarily distracted and calling its cubs over for the meal, the gazelle will pop up suddenly and discharge all of the pent-up frozen energy it has and gallop away virtually unscathed.

In my own explorations into jhana states, the body can get tingly, very pleasant and certain parts of the body even lose sensation. Depending on the type of jhana you are cultivating, the 'one-pointed absorption' jhanas can bring you to a place where you have absolutely no feeling in your body.

From an evolutionary perspective, the dorsal vagal state is exactly what you would want if you were caught by a lethal predator – to lose contact with your body and senses for a period of time so that you would die a painless death. Thanks evolution.1

The point is that if a meditator like Ajahn Chah is in a deep jhana state, then as far as a passing animal is concerned, it’s the equivalent to playing dead! Many predators (wolves, tigers, hyenas etc) prefer to hunt and kill their own prey, so a seemingly dead monk would be of no interest.

What about you?

I think this whole “Buddha vs. Bugs” idea warrants further investigation. Fortunately, I’ll be off for a 1-week nature retreat very soon, so I’ll have plenty of chances to further test this theory in Colorado’s outback.

I’d love to hear from any fellow meditators reading this — what’s your experience meditating in the wild? Meet any cobras?

Lemme know below :) 👇

It makes sense that sitting still and not moving at all for hours and hours would bring you to this sort of freeze state. In a way you are “hacking” your body to do this as a meditator. When the mind is quiet, heart is open, and the body is no longer “in the way,” the reward is deep, mystical experiences and insights.

Of course, the freeze state during a real threat is different than the one experienced in meditating, as it’s one you are going into willingly with meditation (in the same way you can willingly hyperventilate to produce altered states of consciousness). In meditation it feels less like dissociation (but that can happen too) as you are still typically aware of your body.